In the palm of your hand rests a device capable of streaming high-definition video, navigating by satellite, and running complex artificial intelligence models. On your desk sits another, crunching spreadsheets, rendering 3D graphics, and compiling code. While both are quintessential “computers,” the brains that power them—their processors—are engineered for diametrically opposed worlds. The journey of a smartphone System-on-a-Chip (SoC) and a desktop Central Processing Unit (CPU) may begin in the same silicon foundries, but their design philosophies, architectures, and ultimate goals diverge profoundly. Understanding this divide is key to appreciating the silent technological marvels that power our daily lives.

The Core Dichotomy: Integration vs. Raw Power

The most fundamental difference is right there in the names. A smartphone uses a System-on-a-Chip (SoC), while a computer uses a Central Processing Unit (CPU). This is not mere semantics.

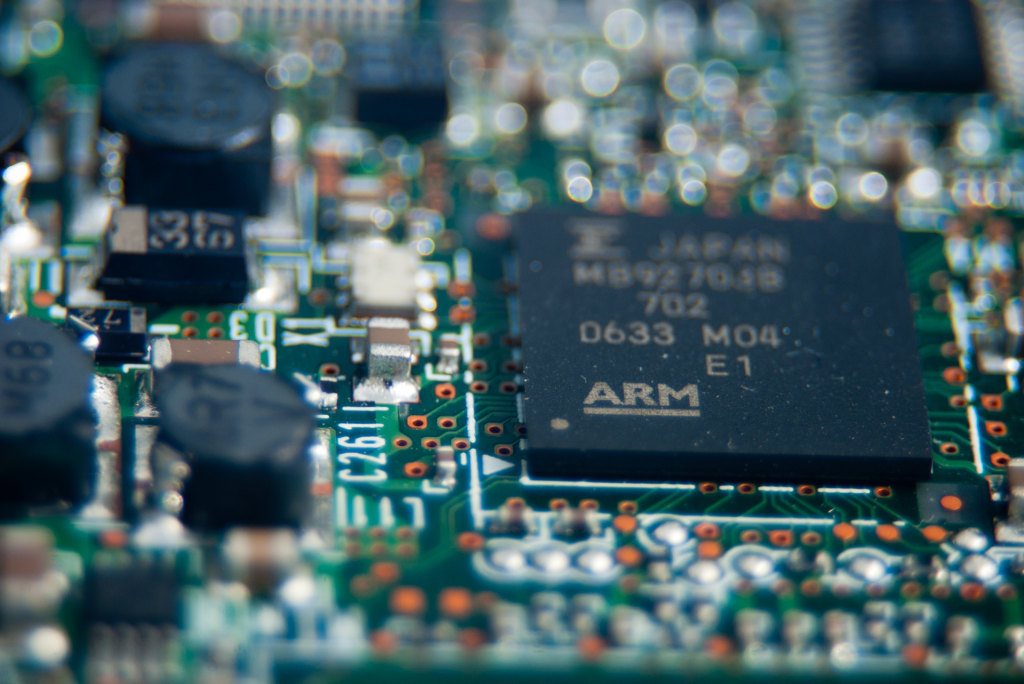

A smartphone SoC is a monument to integration. On a single, tiny sliver of silicon, engineers pack not just the main CPU cores, but also the graphics processing unit (GPU), the image signal processor (ISP) for the cameras, the digital signal processor (DSP) for audio and sensor data, the neural processing unit (NPU) for AI tasks, the modem for cellular connectivity (5G/4G), memory controllers, and more. It’s an entire city of specialized districts built on a nanometer-scale plot. This integration is driven by the paramount constraints of a mobile device: extreme power efficiency and minimal physical space. Every component must work in harmony to sip battery life, not guzzle it.

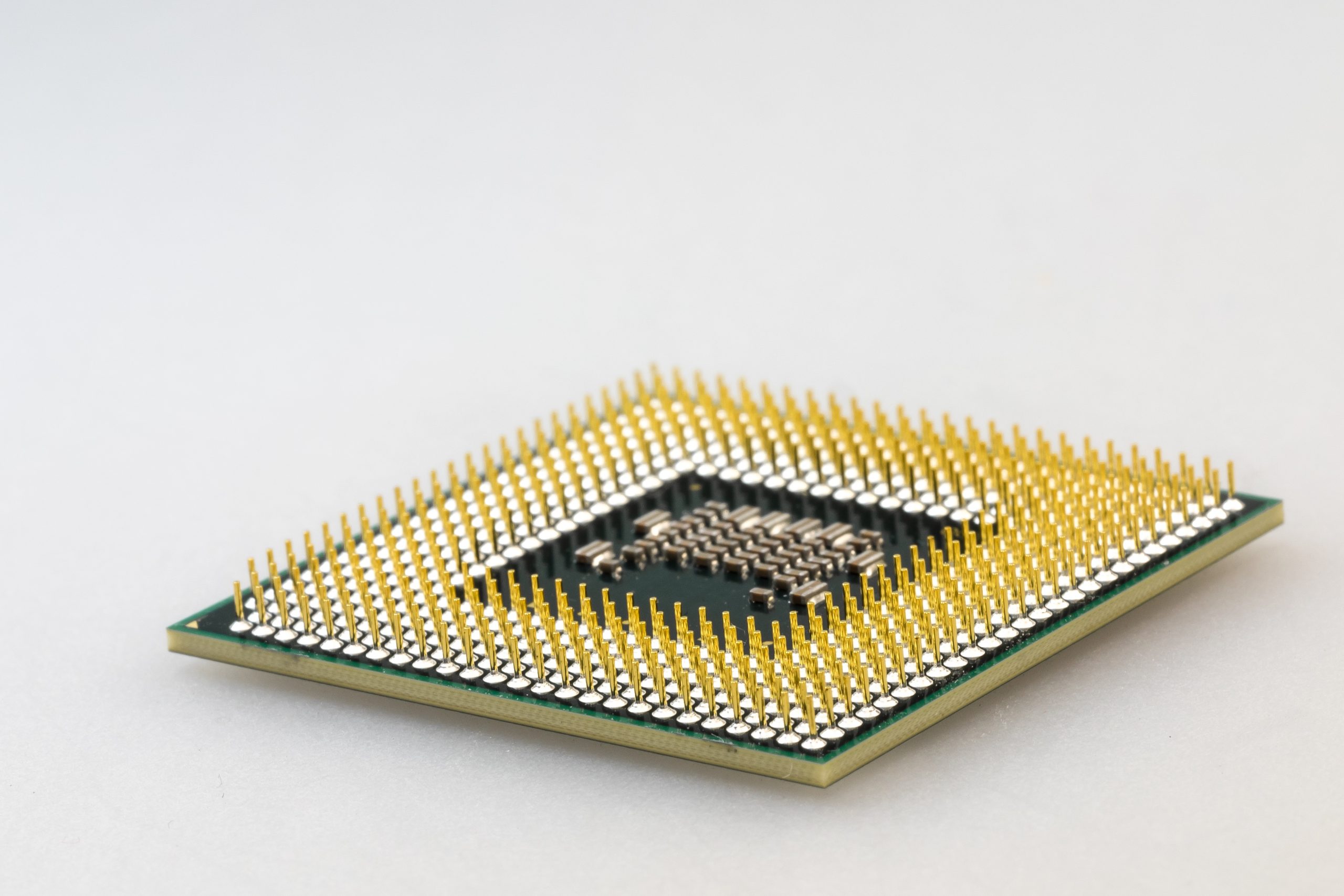

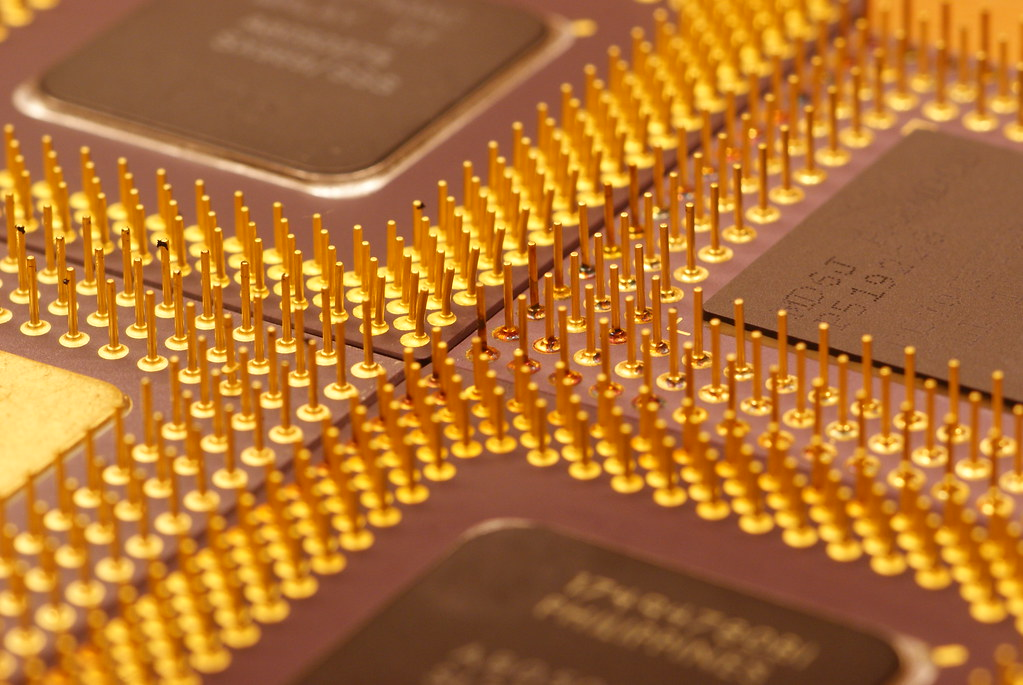

In contrast, a desktop or laptop CPU is a specialist in raw, general-purpose computational throughput. It is typically a discrete chip on a motherboard, connected via high-speed sockets and buses to separate components: dedicated graphics cards (GPUs), separate RAM modules, dedicated sound cards, and a plethora of expansion slots (PCIe). This modularity allows for immense flexibility and power. A user can pair a top-tier CPU with a professional-grade GPU, terabytes of fast storage, and 128GB of RAM. This ecosystem is designed for sustained, high-wattage performance, cooled by large heatsinks and fans, and fed by a continuous power supply.

Architectural Philosophy: Heterogeneous vs. Homogeneous Cores

Dive into the processor cores themselves, and the contrast sharpens. Modern smartphone SoCs are pioneers of heterogeneous multi-core design. An average flagship SoC like the Apple A-series or Qualcomm Snapdragon features a mix of core types: a couple of high-performance “big” cores (for bursty tasks like app launches), several mid-range “medium” cores (for sustained workloads), and multiple ultra-efficient “small” cores (for background tasks). This sophisticated ballet, managed by the operating system and the chip’s own scheduler, ensures the right job goes to the right core, maximizing battery life. The clock speeds are generally lower (topping out around 3-4 GHz) to control heat and power consumption.

Computer CPUs, until recently, primarily relied on homogeneous multi-core designs—multiple cores of the same, powerful architecture. While modern Intel and AMD chips now also incorporate hybrid architectures (like Intel’s P-cores and E-cores), the scale is different. The performance cores are vastly more complex and powerful, built on architectures that prioritize instruction-level parallelism and high clock speeds (often pushing 5-6 GHz with turbo modes). They are designed to handle intensive, single-threaded tasks (like gaming physics or old software) with blistering speed, as well as massively parallel workloads across many cores (like video encoding). They achieve this by drawing significantly more power—where a phone SoC might have a total thermal design power (TDP) of 5-10 watts, a desktop CPU can consume 65 to over 300 watts.

The Graphics Divide: Integrated vs. Discrete

Graphics processing highlights another key distinction. In a phone SoC, the GPU is an integrated part of the chip. While incredibly efficient and capable (driving stunning mobile games and high-resolution displays), it shares the SoC’s limited thermal budget and memory bandwidth with every other component. It’s a master of efficiency, not raw graphical might.

Computer processors can have integrated graphics (iGPUs), similar to an SoC’s GPU, but the high-performance path is the discrete Graphics Processing Unit (dGPU). A dedicated graphics card like those from NVIDIA or AMD is essentially a supercomputer for parallel tasks, with its own dedicated, high-speed memory (VRAM), its own power delivery, and a massive cooling system. This allows it to render complex 3D worlds, perform scientific simulations, and accelerate AI training at a scale unimaginable for any mobile device.

Memory and Connectivity: A Tale of Two Bandwidths

Memory is another differentiator. Smartphones use LPDDR (Low-Power Double Data Rate) RAM, which is soldered directly onto the SoC package or motherboard. This achieves remarkable space and power savings but offers lower overall bandwidth and zero upgradability. The entire SoC, including the CPU and GPU, shares this single pool of memory.

Computers use standard DDR RAM modules, which are socketed, allowing for easy upgrades. The bandwidth to the CPU is significantly higher, crucial for feeding data-hungry cores. Furthermore, with a discrete GPU, the graphics data flows over an ultra-fast PCIe bus to the GPU’s own dedicated VRAM, creating a two-tiered, high-bandwidth memory system that decongests the data flow.

Connectivity is also baked into the SoC (Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, GPS, Cellular), whereas on a computer, many of these functions are handled by separate chips or expansion cards, again emphasizing modularity and choice.

The Convergence and The Unchangeable Truth

The lines are blurring in fascinating ways. Apple’s M-series chips for Macs are essentially supercharged SoCs, bringing smartphone-like integration, incredible efficiency, and powerful unified memory to the laptop world. Conversely, smartphone SoCs are incorporating ever more powerful NPUs and ISPs, handling AI and computational photography tasks that would have required a desktop a decade ago.

Yet, the core physical constraints remain immutable. A smartphone processor will always be a champion of efficiency per watt, designed for a life of mobility within a strict thermal envelope. A desktop processor will always be a champion of unbridled, plug-in-the-wall performance, designed for expandability and sustained heavy lifting. One is a Swiss Army knife—exquisitely engineered, compact, and perfectly suited for a thousand daily tasks. The other is a workshop full of specialized, high-powered tools—bulkier, hungrier, but capable of reshaping digital reality itself.

In the end, the difference is not about which is “better,” but about a brilliant divergence in engineering to serve two different manifestations of the computing dream: one fits in your pocket to connect you to the world, the other sits on your desk to empower you to shape it.